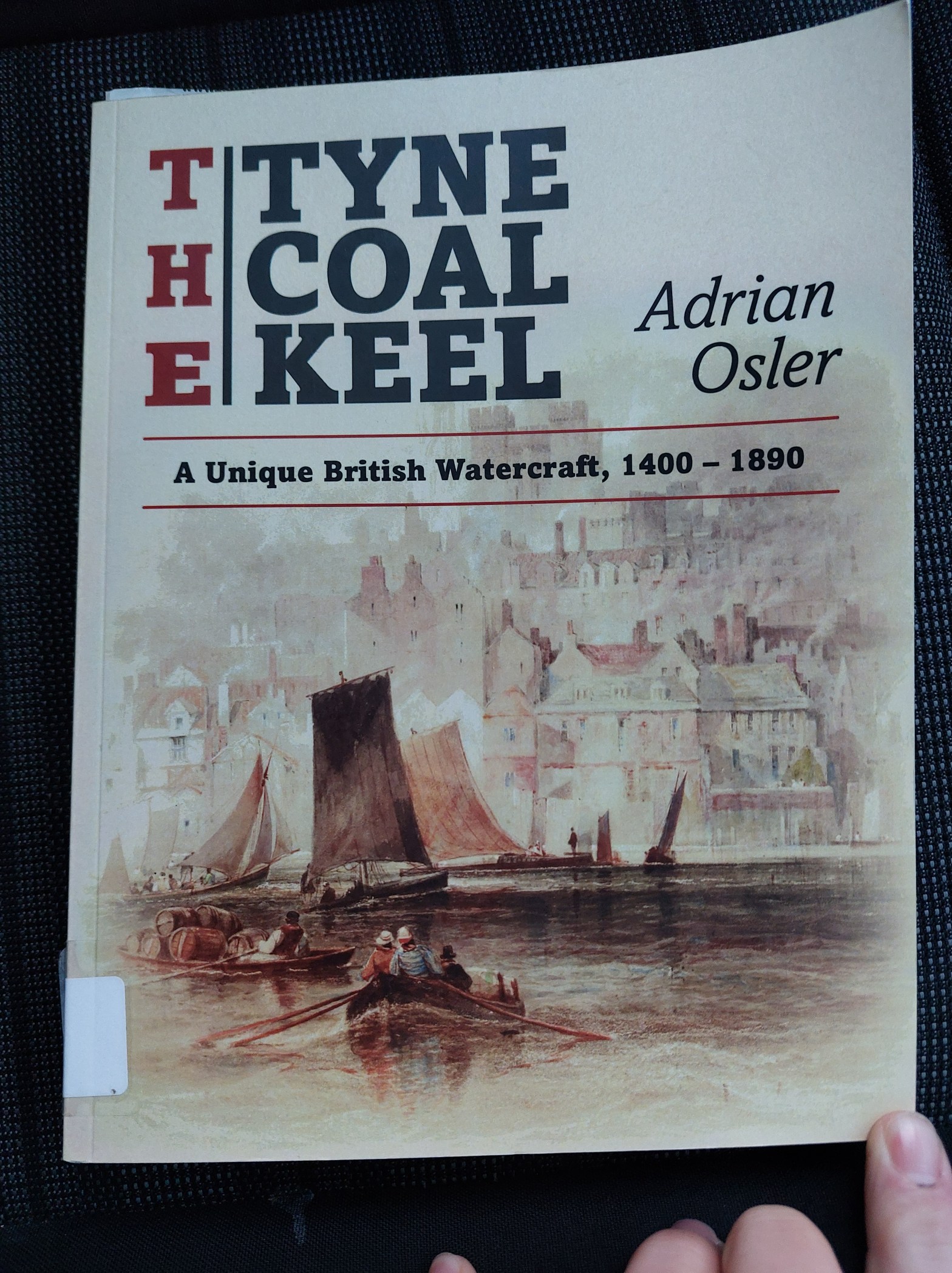

A recent loan from my local library has been ‘The Tyne Coal Keel’ (2022) by Adrian Osler, which whilst only partially read so far, is a fascinating book with some initial facts that, in my view, are clearly worth sharing more widely as part of the knowledge of these interesting small vessels that have long-since disappeared.

While many associate the early railways, and before that the waggonways with carrying coal from pit to port, and loading directly into ships (colliers) via staiths, the Keel was actually a surprisingly important part of the overall transport of coal from pit to hold of the ship, which I feel I have overlooked myself somewhat!

So just what is a Tyne Coal Keel?

Carrying coal doon the Tyne

The Tyne Coal Keel is a relatively small river craft that would take the load of eight ‘Newcastle Chaldrons’ worth of coal, equivalent to 21.2 tons (21540 kg) (Olser (2002 p.12), this limit being set by law.

The purpose of a Keel was in short, a solution to the problems of a very shallow and tidal river Tyne; larger colliers would run the risk of grounding with the combination of low tide and sitting low in the water with a hold full of coal, and in the upper stretches of the tyne, access was restricted by the river being more shallow, as well as the presence of the old Tyne Bridge (where the swing bridge is now).

The early waggonways, effectively all wooden railways using wooden, horse drawn waggons filled with coal were often built on the shortest and/or cheapest route from a pit to the riverside, with each pit, or group of pits under the same owner having its own waggonway, set to its own gauge (there was no ‘standard’ size for a waggonway, the standard gauge of today (4ft 8.5in/1435mm) is thought to be just one waggonway gauge being adopted for the then new railways by Stephenson and becoming pretty much the international standard over time.).

There was something of a logic behind waggonways being laid to different gauges though; as it meant that each colliery or group of colleries had control of its own waggonway from pit to riverside, you couldn’t use other waggons was they wouldn’t fit on the waggonway (the gauge being too wide or too narrow), but did result in waggons being ‘captive’ within their own small system, either a single route between a pit and the riverside staith or loading point, or a few interconnected collieries.

This did mean, especially for upriver pits, that getting coal from pit to collier wasn’t possible directly, so the coal needed to be transhipped into a waiting keel, eight chaldrons worth of it, then sailed down the river on these small vessels, then transhipped again from the keel into the waiting collier, and once the collier was filled, off it sailed out the Tyne bound for London or elsewhere.

The Coal Carrying Paradox?

The Keel was part of shipping coal down the Tyne for about 600 years (c.1350 to c.1850) again by Osler (2022 p. 12), but the exact layout and dimensions of this important and long-lived watercraft isn’t recorded well as Osler defines in his book, sadly the ‘HGV’ of its day wasn’t well recorded by comtemporary sources.

Putting that in context, the Tyne Coal Keel as a vessel operated from around the reign of King Edward III, who lived through the Black Death, and lasting until the early reign of Queen Victoria; and the first century of their operation was around the time of the Hundred Years War, which I think helps to contextualise their longevity as a river craft.

The fleet of keels is also thought, at their peak, to have numbered several hundred, but technological advancements in railways, staiths, and shipping rendered them quickly obsolete, with them becoming extinct shortly afterwards.

The combination of a standard railway gauge and a proper, interconnected network of railways meant that coal could travel in ever larger waggons, hauled by steam locomotives across shared tracks, making their way towards a much larger, more substantial staith serving ever larger vessels, especially as steam began to replace sailing ships, dredging of the river allowed larger ships with a larger draught to reach inland staiths such as at Dunston.

An interesting paradox that Osler (2022 p. xxi) puts forward is that the actual transport of coal until the steam era often relied on mostly renewable means; horse drawn waggons, gravity inclines, tides, sail and oar powered keels and sailing colliers meant that getting coal from the pit to the furnace or the fireplace was actually quite a clean process in many ways until the coal was itself burnt.

With the demand for coal surging and the advancement of steam technology, a greater amount of mined coal would need to go into the transport of itself; fuel for winders, locomotives, and colliers, meaning that many tons of coal might already have been burnt before the vessel sailed through out of the mouth of the Tyne fully laden, compared to the sailing colliers of earlier years where perhaps a small amount may have been burnt for a winding engine, but the rest done by renewable sources of gravity, muscles of man and horse, tidal, and wind power.

It is a very interesting book, and well worth a read if you enjoy the heritage of North East England, and especially its industrial heritage.